Bruker Emission FTIR measurements

Updated:

Short description of results from emission measurements

Bruker agreed to perform some emission FTIR measurement on various samples. One of the goals is to see if this can help explain why it has been so difficult to differentiate between the plastic samples and why POM is so spectrally “outstanding”.

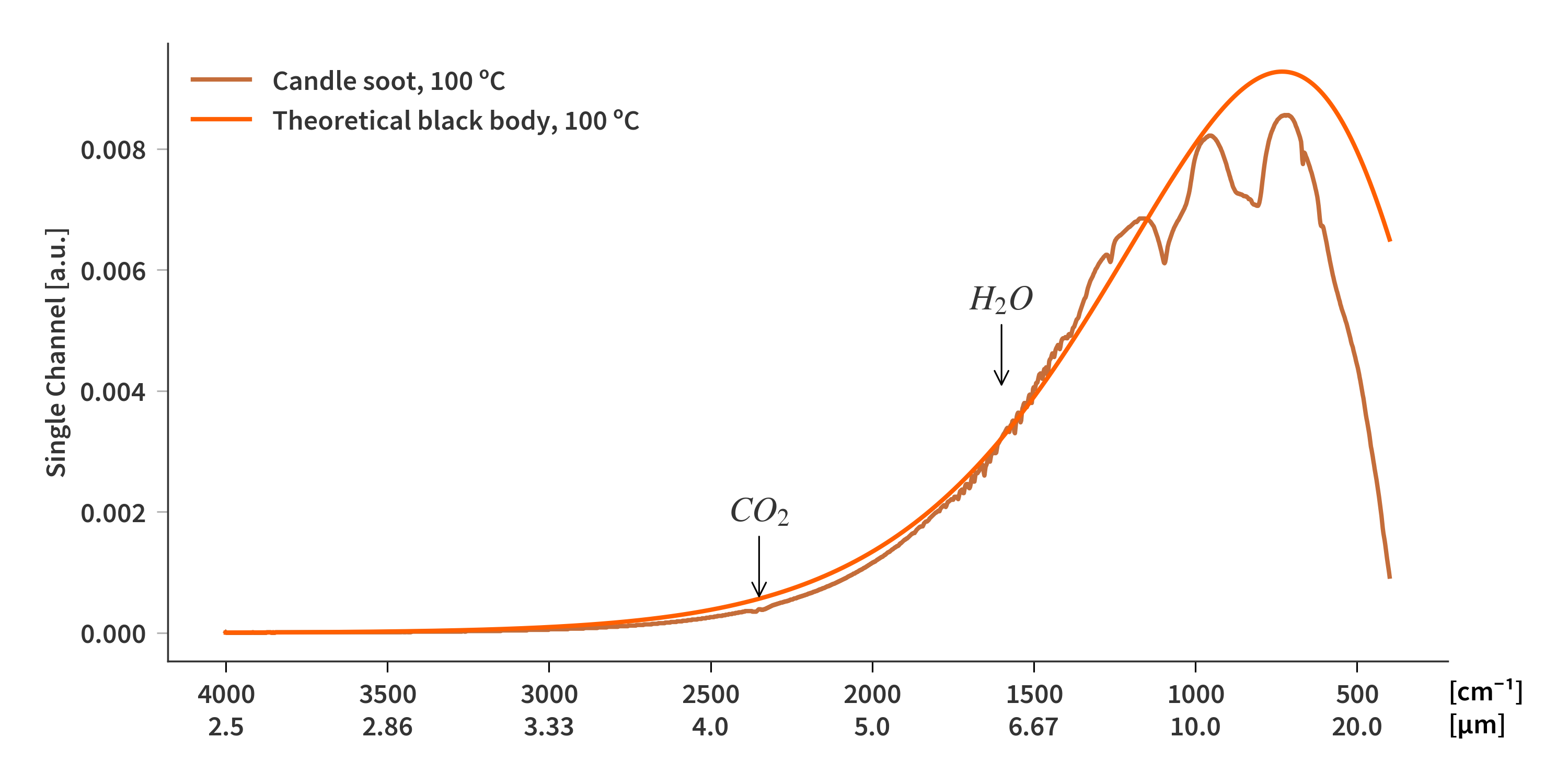

The emissivity of the samples is estimated based on a reference black body. In this case, Bruker opted for candle soot as this should have a rather flat spectral emissivity. Fig. 1 show the comparisons between the candle soot reference measurement and a theoretical black body curve. The larger deviations are probably due to the instrument instrument. Some of the typical absorption lines from water and $\textrm{CO}_2$ are visible (albeit only small contributions). The larger peaks I think is due to the response of the detector as it is also seen in many of the other samples depicted in Fig 2.

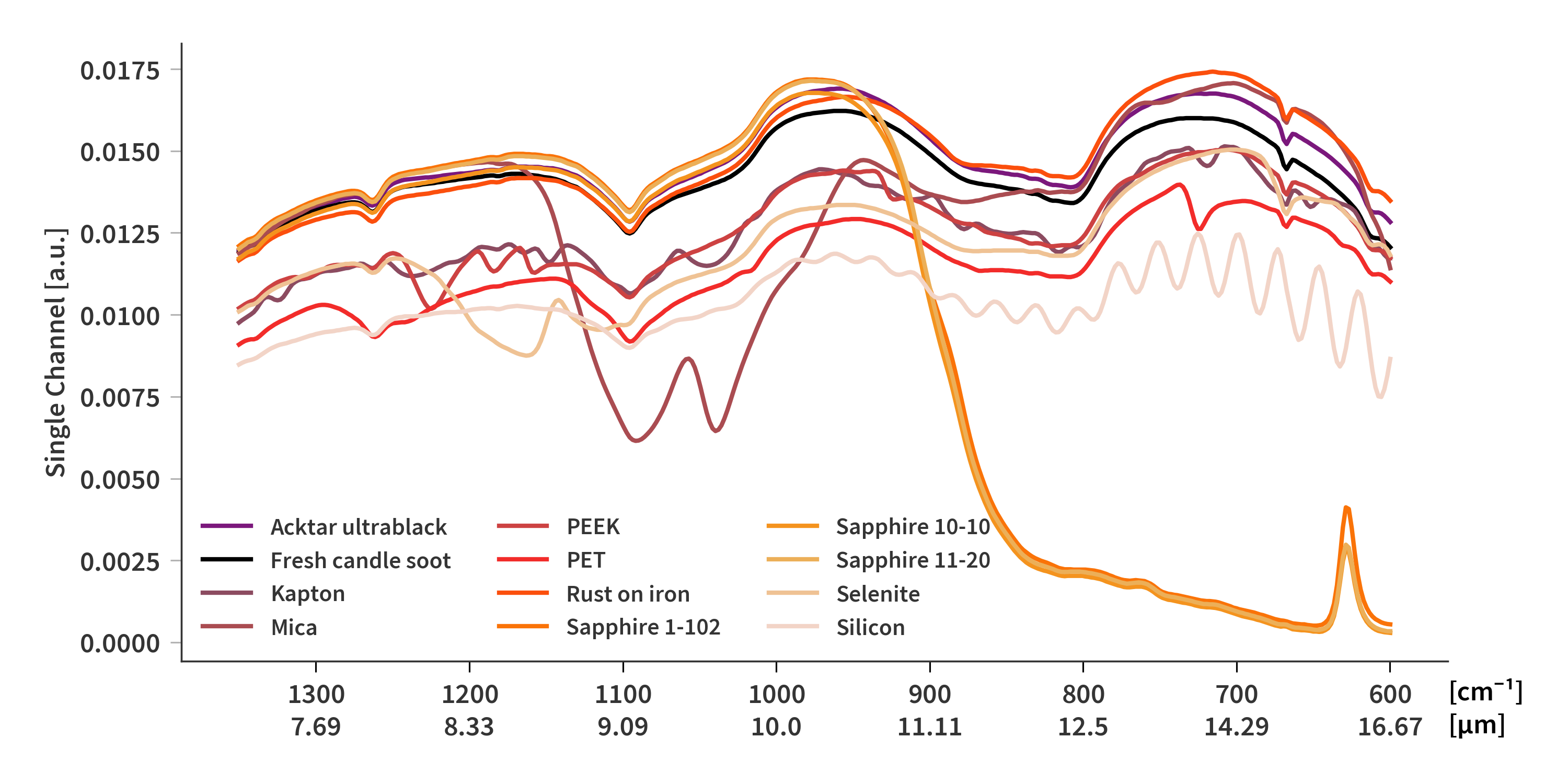

In theory, as long as the reference is a “true” black body, the instrument characteristics should disappear when calculating the emissivity… But a perfect black body is too much to ask for in practice as many of the other sample actually turn out to have even higher emissivity than the reference sample (Fig. 2). Rust and Acktar Ultrablack would all seem to be good choices for new reference samples, but in these measurements, Bruker stuck with the candle soot (I guess because they know it spectrally).

Single channel measurements of all samples can be found here. The emissivity of most samples have been calculated based on the single channel measurements and can be found here.

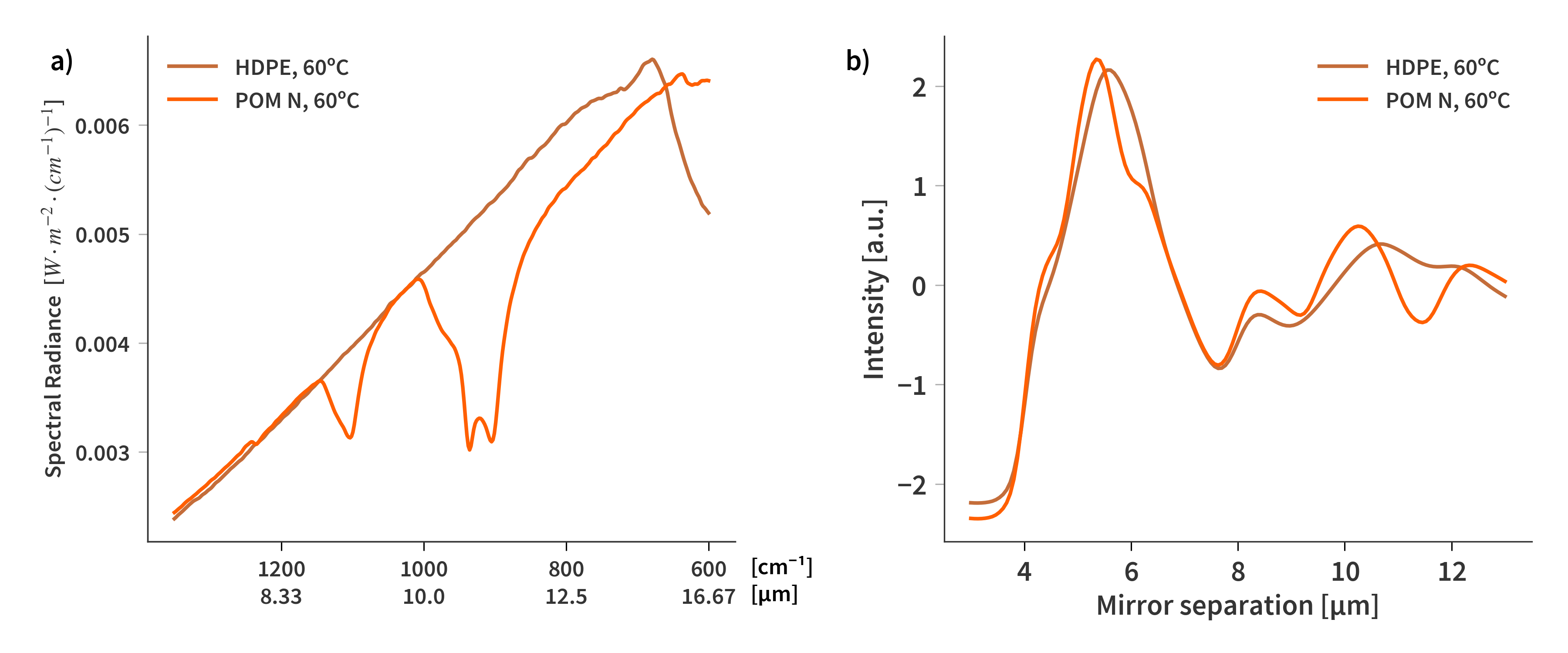

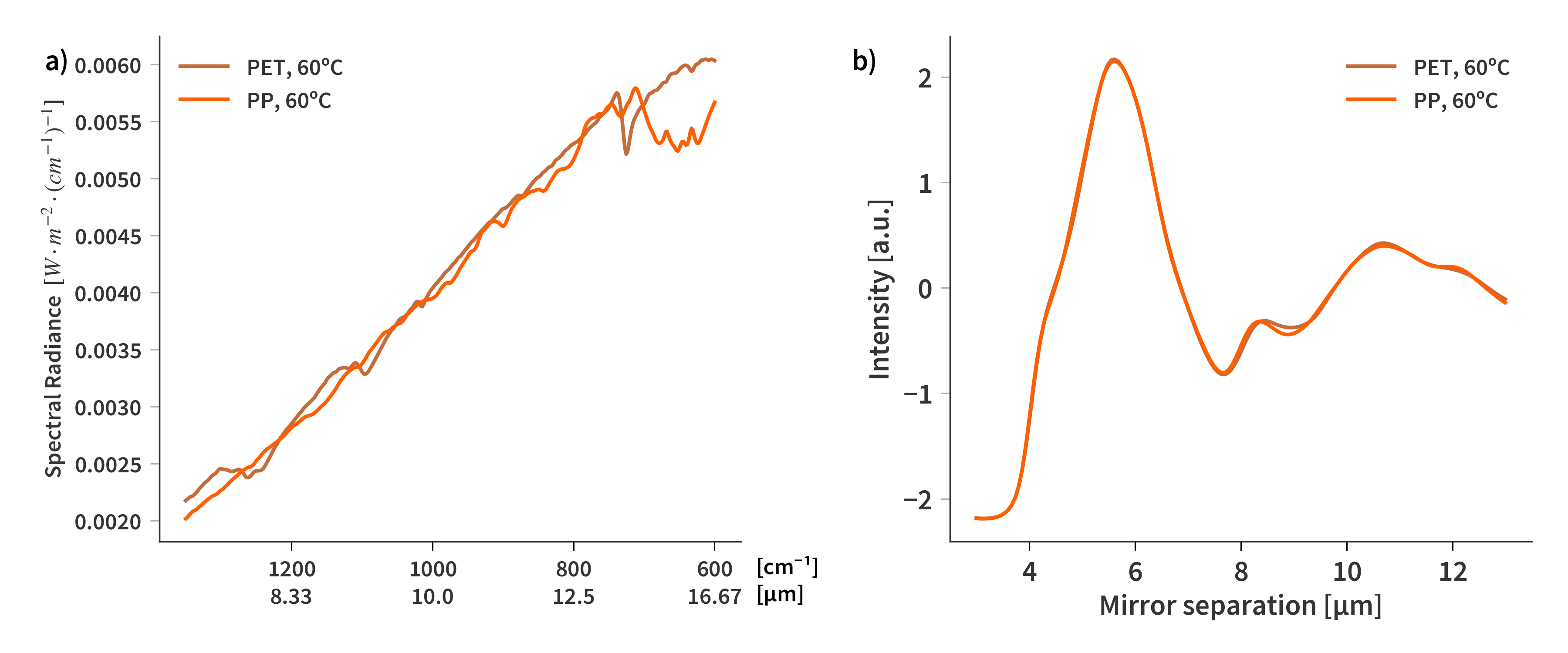

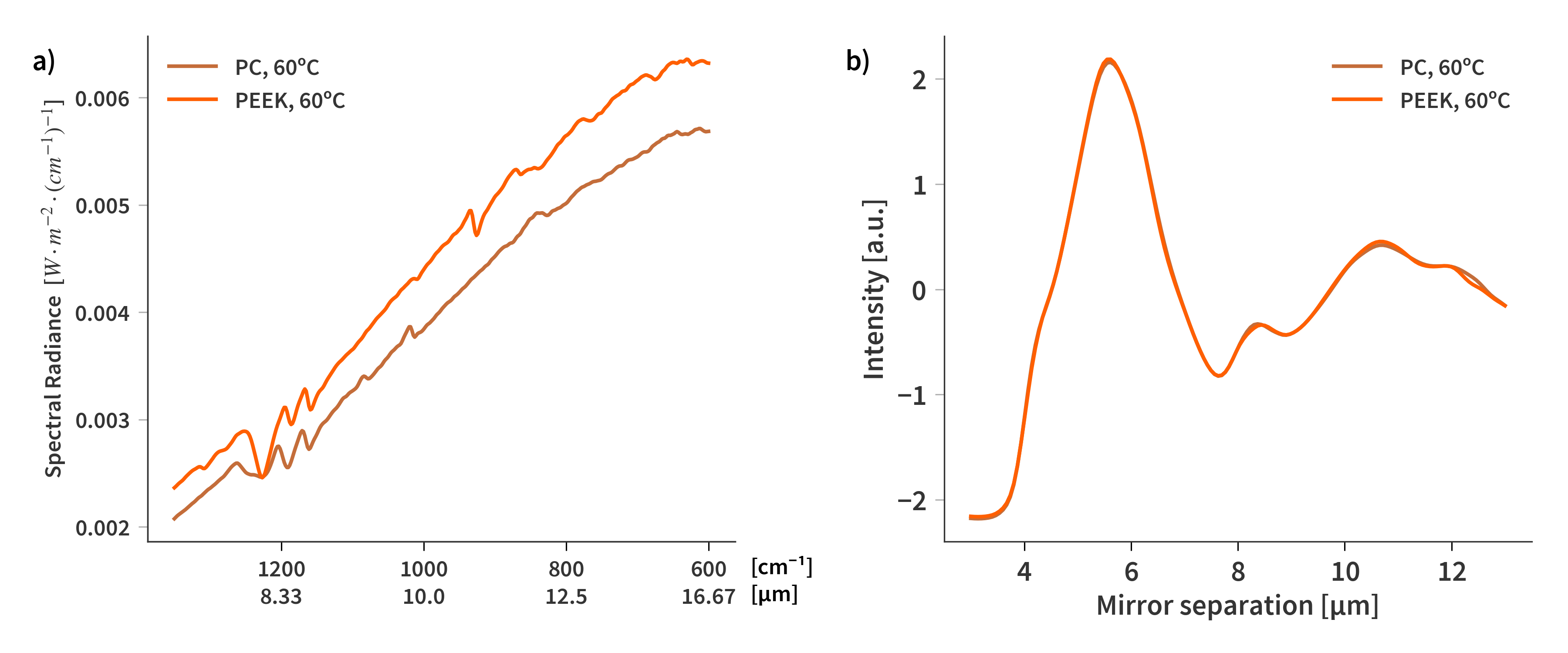

Fig. 3, 4, and 4 depict the theoretical emission spectra (emissivity multiplied with black body) and simulated interferograms. Here we notice why POM has been so easy to recognize compared to the other plastics. It has much larger variations in its emission spectrum, and as it has previously been hypothesized (here), the absorption/emission lines of the other plastics are obscured by the black body emission - the signal variations are simply too week comparatively. To enhance the differences between the plastics, Acktar Ultrablack was used as a reference sample in the measurements from Aarhus. For all plastics except POM, the interferograms more or less look like that of a black/grey body emitter which is also what was observed experimentally. The spectral features of POM also line up with what has previously been seen.

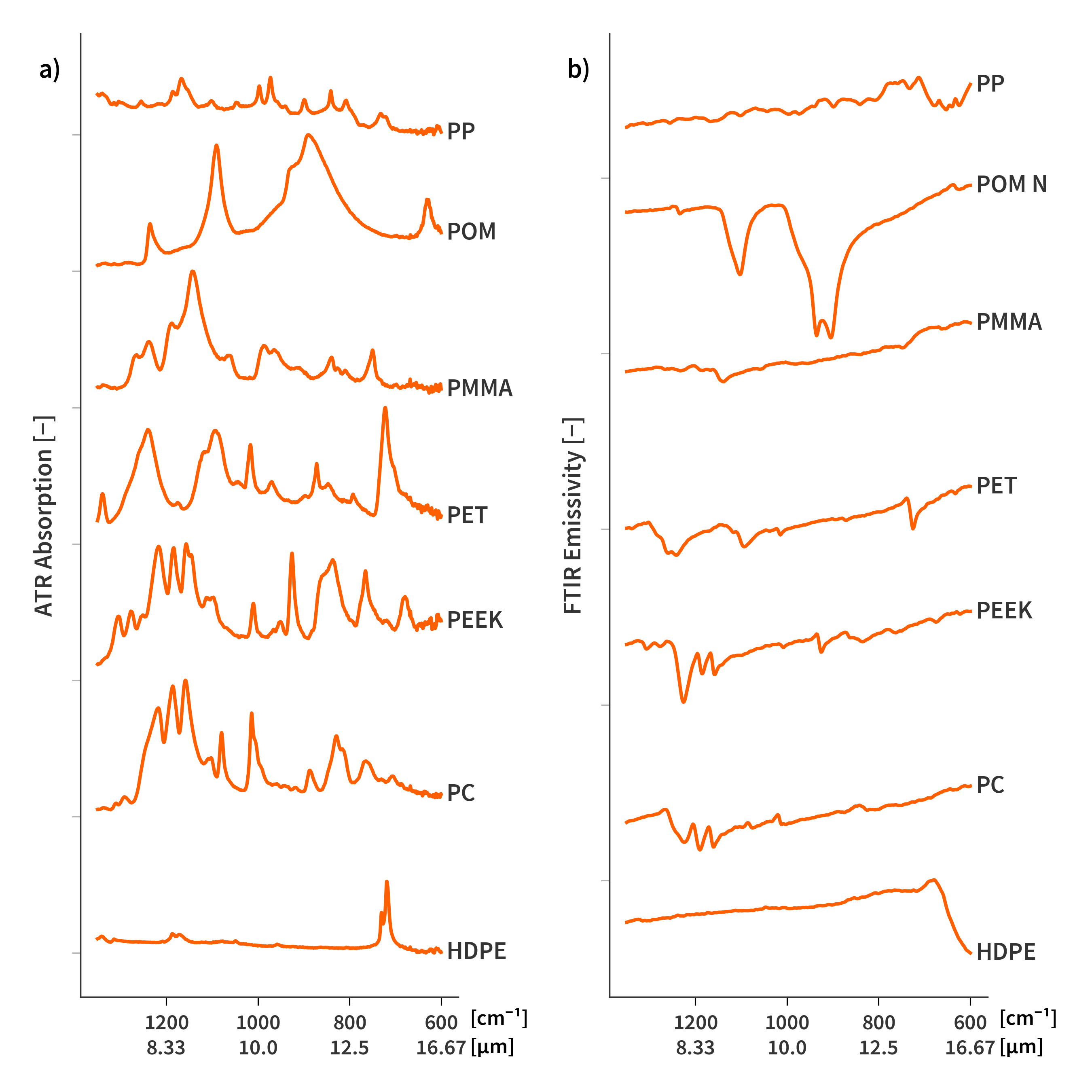

If we compare the ATR measurements from Aarhus (Fig. 6) with the emission measurements, we also see that ATR absorption cannot replace the emissivity measurements. They appear to not be capturing the same thing. However, I find it difficult to evaluate how much the spectral profile of the candle soot influences the emissivity measurements. If it is spectrally flat, then it is only an offset in the emissivities, but since it is a reference, it can add some features of its own.